DNA replication

Definition: the process of copying a parental DNA molecule to form two daughter DNA molecules.

- Introduction to DNA replication

- DNA replication is essential for cell proliferation, i.e. mitosis, meiosis.

- DNA replication is a complex endeavor involving a series of enzyme activities.→see “DNA polymerases”

- DNA replication is performed in a semiconservative and semidiscontinuous mode.→see “DNA replication is semi-conservative”

- DNA replication has 3 stages: initiation, elongation and termination.→next section

- DNA replication is tightly regulated, involving various protein-protein, protein-DNA interactions.

- DNA replication of prokaryote and eukaryote shares similar features, but is distinctive in details.

- Chemical Reaction of DNA replication

Essentials

2. Template: a primer-template junction

- DNA polymerases

- DNA polymerase I

- Pol I was the first enzyme discovered with polymerase activity, and it is also the best characterized one.

- Although abundant in cells (400/cell), Pol I is NOT the primary enzyme involved with bacterial DNA replication.

- Main functions of Pol I: (1) Fill any gaps in the new DNA that result from the removal of the RNA primer by its 5’ -3’ polymerase activity; (2) Remove a new mispaired base by proofreading (校读)3’-5’ exonuclease (外切酶) activity. (3)Remove the RNA primer by its 5’-3’ exonuclease activity

The 3′–>5′ exonuclease activity intrinsic to several DNA polymerases plays a primary role in genetic stability; it acts as a first line of defense in correcting DNA polymerase errors. A mismatched basepair at the primer terminus is the preferred substrate for the exonuclease activity over a correct basepair. (source)

- DNA polymerase III

- The primary polymerase in DNA replication, although lower in abundance (15/cell)than pol →referred to as “replicase”

- functions: (1) 5’→3’ polymerase activity; (2) 3’→5’ exonuclease activity – proofreading

- Catalytic efficiency: much higher than pol I→High processivity and polymerization rate

- A multi-unit complex: “holoenzyme” (全酶)

- DNA replication is semi-conservative

Bet you all have learned it in high school, and the famous experiment by Meselson and Stahl. We still need to go over the points again as they are essentially important for what we will learn next.

The key to the mechanism of DNA replication is the fact that each strand of the DNA double helix carries the same information-their base sequences are complementary (we talked about this in THE BLUEPRINT OF LIFE [2]: PRIMARY AND SECONDARY STRUCTURE OF DNA).

During replication, the two parental strands separate and each acts as a template (that’s right, the template for DNA replication is DNA itself!)to direct the enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of a new complementary daughter strand with the normal base-pairing rules (A-T, C-G)

This semi-conservative mechanism was demonstrated experimentally in 1958 by Meselson and Stahl.

Hypotheses:

In the experiment:

E. coli cells were grown for several generations in presence of the stable heavy isotope 15N so that their DNA became fully density labeled (both strands are 15N labeled: 15N/15N)

The cells were then transferred to medium containing only normal 14N and, after each cell division, DNA was prepared from a sample of the cells and analyzed on a CsCI gradient using the technique of equilibrium (isopycnic) density gradient centrifugation, which separates molecules according to differences in buoyant density.

After the first cell division, when the DNA had replicated once, it was all of hybrid density, in a position on the gradient half way between fully labled (15N /15N )and fully light (14N/14N). After the second generation in 14N, half of the DNA was hybrid density and half fully light.

Thus, two of the hypotheses were denied, left us with the semi-conservative mechanism.

After each subsequent generation, the proportion of 14N/14N increased, while some DNA of hybrid density persisted. Thus the semi-conservative mode of DNA replication is confirmed: each daughter molecule contains one parental strand and one newly-synthesized strand.

![the blueprint of life [11]: DNA replication 1](https://apbiology.cn/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2014/01/cropped-Epeorus-Melli..jpg)

![Mendel’s Genetics [6]: Examples of epistasis](https://apbiology.cn/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2013/12/genetics-3-snapdragons.jpg)

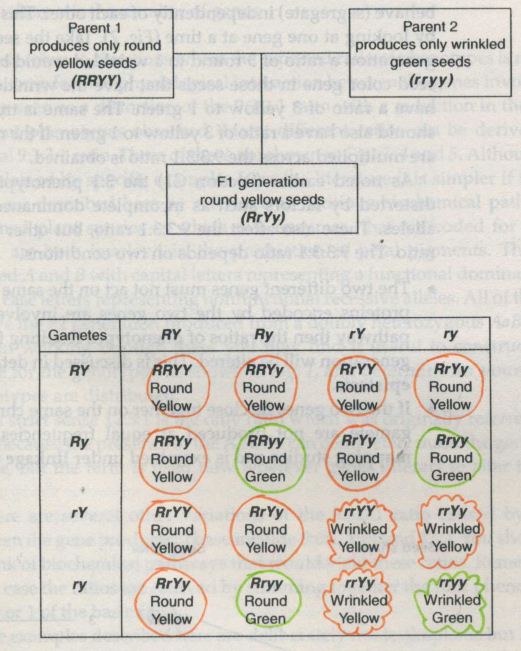

![Mendel’s Genetics [5]: The dihybrid cross](https://apbiology.cn/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2013/07/genetics2.png)